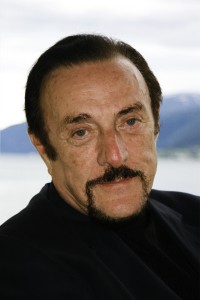

Dr. Philip Zimbardo, Psychology Professor Emeritus at Stanford University

This interview was a rare and inspirational privilege to speak with world-renowned psychologist and Stanford Emeritus Professor Phil Zimbardo (most recently Founder and President of the Heroic Imagination Project), together with Brooke Deterline, Director of Corporate Consulting for the Heroic Imagination Project. The central theme: How Dr. Zimbardo’s over 40 years of ground-breaking and history-changing research on how good people can become susceptible to engaging in evil conduct applies in contemporary organizations and society – and how individuals can face challenging situations and systems that drive many toward evil but now act with courage or “contemporary heroism.” How can heroes of all ages come out of decades of research on evil? Dr. Philip Zimbardo, World-Renowned Psychologist and Professor Emeritus at Stanford University Dr. Philip Zimbardo is one of the world’s most distinguished living psychologists, having served as President of the American Psychological Association, designed and narrated the award winning 26-part PBS series, Discovering Psychology, and has published more than 50 books and 400 professional and popular articles and chapters, among them, Shyness, The Lucifer Effect, and The Time Paradox. A professor emeritus at Stanford University, Dr. Zimbardo has spent 50 years teaching and studying psychology. He received his Ph.D. in psychology from Yale University, and his areas of focus include time perspective, shyness, terrorism, madness, and evil. He is best-known for his controversial Stanford Prison Experiment that highlighted the ease with which ordinary intelligent college students could cross the line between good and evil when caught up in the matrix of situational and systemic forces. Brooke Deterline, Corporate Director for the Heroic Imagination Project As Corporate Director for the Heroic Imagination Project (HIP), Brooke helps boards, executives, and teams at all levels develop the skills to act with courage and ingenuity in the face of challenging situations. This fosters leadership credibility and candor, builds trust, engagement and reduces risk. Brooke believes strongly (and years of research back it up) that you can do better by doing good. Prior to her work at Heroic Imagination Project, Brooke co-founded StreetSmart IR, a San Francisco-based investor relations firm. She’s worked in corporate social responsibility (CSR), combining her strategic focus with her passion for sustainability, leadership, empowerment, and social and environmental justice. Brooke started as a journalist at SmartMoney magazine and is a trained mediator. The Heroic Imagination Project (HIP) is a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization that teaches people how to overcome the natural human tendency to watch and wait in moments of crisis and to create meaningful and lasting change in their lives. Headquartered in San Francisco, California, The Heroic Imagination Project translates the extensive research findings of Dr. Philip Zimbardo, Professor Emeritus of Psychology at Stanford University, into meaningful insights that individuals can use in their everyday lives to transform negative situations and create positive change. Dr. Zimbardo’s groundbreaking work has studied the psychological foundations of negative forms social influence forces (such as conformity, obedience, and the bystander effect) and is now refocused on understanding the nature of everyday heroism and they psychology of personal and social growth. HIP recently won the Ashoka/Townsend Press Prize in the Activating Empathy competition. HIP was highlighted as an innovator bringing the skill of empathy to students in transformative ways.

This interview was a rare and inspirational privilege to speak with world-renowned psychologist and Stanford Emeritus Professor Phil Zimbardo (most recently Founder and President of the Heroic Imagination Project), together with Brooke Deterline, Director of Corporate Consulting for the Heroic Imagination Project. The central theme: How Dr. Zimbardo’s over 40 years of ground-breaking and history-changing research on how good people can become susceptible to engaging in evil conduct applies in contemporary organizations and society – and how individuals can face challenging situations and systems that drive many toward evil but now act with courage or “contemporary heroism.” How can heroes of all ages come out of decades of research on evil? Dr. Philip Zimbardo, World-Renowned Psychologist and Professor Emeritus at Stanford University Dr. Philip Zimbardo is one of the world’s most distinguished living psychologists, having served as President of the American Psychological Association, designed and narrated the award winning 26-part PBS series, Discovering Psychology, and has published more than 50 books and 400 professional and popular articles and chapters, among them, Shyness, The Lucifer Effect, and The Time Paradox. A professor emeritus at Stanford University, Dr. Zimbardo has spent 50 years teaching and studying psychology. He received his Ph.D. in psychology from Yale University, and his areas of focus include time perspective, shyness, terrorism, madness, and evil. He is best-known for his controversial Stanford Prison Experiment that highlighted the ease with which ordinary intelligent college students could cross the line between good and evil when caught up in the matrix of situational and systemic forces. Brooke Deterline, Corporate Director for the Heroic Imagination Project As Corporate Director for the Heroic Imagination Project (HIP), Brooke helps boards, executives, and teams at all levels develop the skills to act with courage and ingenuity in the face of challenging situations. This fosters leadership credibility and candor, builds trust, engagement and reduces risk. Brooke believes strongly (and years of research back it up) that you can do better by doing good. Prior to her work at Heroic Imagination Project, Brooke co-founded StreetSmart IR, a San Francisco-based investor relations firm. She’s worked in corporate social responsibility (CSR), combining her strategic focus with her passion for sustainability, leadership, empowerment, and social and environmental justice. Brooke started as a journalist at SmartMoney magazine and is a trained mediator. The Heroic Imagination Project (HIP) is a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization that teaches people how to overcome the natural human tendency to watch and wait in moments of crisis and to create meaningful and lasting change in their lives. Headquartered in San Francisco, California, The Heroic Imagination Project translates the extensive research findings of Dr. Philip Zimbardo, Professor Emeritus of Psychology at Stanford University, into meaningful insights that individuals can use in their everyday lives to transform negative situations and create positive change. Dr. Zimbardo’s groundbreaking work has studied the psychological foundations of negative forms social influence forces (such as conformity, obedience, and the bystander effect) and is now refocused on understanding the nature of everyday heroism and they psychology of personal and social growth. HIP recently won the Ashoka/Townsend Press Prize in the Activating Empathy competition. HIP was highlighted as an innovator bringing the skill of empathy to students in transformative ways.

- What is the most important ethical lesson you have learned (either personally or professionally)?

PZ: In any situation where someone is trying to convince you to do something, it is critical to pause and do a situational analysis. This might mean assessing a corporate decision or being “street smart” in a rough neighborhood. Then decide explicitly: (i) What is the right thing to do (usually the hardest)? and (ii) What is the expedient thing to do (which may be right or wrong)? Then make a clear decision – clear of semantics, of a boss putting his arm over your shoulder to bring you into the team, of any other verbal or non-verbal influences. With this approach, if an unethical choice is made, it can be acknowledged and remedied. Also, never forget that one person’s decision can influence the final outcome of the majority. In that old infamous Stanford Prison Experiment, it would have taken only one student to halt the experiment, even by bursting out laughing and saying it was all ridiculous.

BD: It was very humbling to see that even though I am generally able to speak up to authority effectively, I had an experience that taught me that I, too, was vulnerable to joining an unethical group reaction. I almost convinced myself to join others in a senior corporate group in supporting a Chief Financial Officer’s ethically questionable decision regarding use of non public information. Fortunately, in the example, the CFO got called away for a minute. I used that lucky pause to reflect and realize that it was “one of those moments” and to connect to my values and training and challenge the proposed decision. What has stayed with me from the experience is a deep understanding of our innate human vulnerability to powerful situations and the need to always be vigilant in assessing situations.

- What is the most shocking corporate ethics matter you have seen in the news recently? Non-profit sector? Why?

PZ: The big evil is systemic and crosses all sectors: governments, multi-national corporations, the multi-lateral organizations… Three key examples are: (i) sex trafficking (one of the biggest businesses in the world – but no systematic international effort to stop it); (ii) arms sales (the US leading in sales to both sides of conflicts, together with all of the major industrialized countries); and (iii) cigarette companies selling a product that is harmful to health and even causing death (including US companies shifting sales to overseas markets with the decline in smoking in the US and the Chinese government-owned company funding schools with cigarette profits and encouraging smoking/discouraging anti-smoking campaigns). One of the factors in assessing these and other evils is reasonable protection of the freedom of the individual. However, individual freedom should not be at the expense of infringing on the freedoms and rights of others. Various dangerous behaviors leading to skyrocketing healthcare costs and tax revenue drain is one example (restricted smoking zones, or wearing motorcycle helmets).

BD: In the non-profit sector, the Penn State child sex abuse scandal that ricocheted around the University and the country is the most shocking. Some of the people involved were not bad people, but rather part of a culture of silence and diffusion of responsibility. For example, there is important research on issues such as the need to support candor in the work place and how pressure-filled situations often result in the ethical implications of our actions to fade from our minds, starting the first step down the slippery slope. Based on the voluminous research, organizations that utilize social and behavioral psychology often outperform their peers, rather than considering it “soft” and not real skills.

In healthcare, major healthcare organizations suffer from dangerous hierarchy resulting in nurses not standing up to doctors. This is especially the case in unusual situations. A recent experiment involving a new doctor from another hospital ordering a prescription that nurses knew could be potentially lethal still resulted in 21 out of 22 nurses giving the patient the dose ordered.

In the for-profit sector, the examples are endless.

- What do you see as the opportunities for the corporate sector and non-profit sector to collaborate in raising the bar in ethical matters?

PZ: There are exciting projects under way involving corporations, academic institutions, non-profit organizations, and even city governments to pursue the mission of developing contemporary heroism – i.e., individuals “with firmly held ethics and the courage to act on them”. Some are even geared to addressing broad cultural and societal changes such as increasing the sense of potential of young people to act heroically within a society – challenging long-standing negative social influences. These can be followed on the HIP web site.

- What are the most effective strategies for mitigating risk of unethical behaviour in your organization?

BD: Never think you are above ethics transgressions. We are all vulnerable, and the experts are almost worse because they are blindsided and because others expect them not to struggle with ethics issues. It is crucial to understand patterns (e.g. not being comfortable sharing bad news). We all have patterns. By sharing them and working on them we can depersonalize and address them. Mostly this is not a question of character but rather situational influence. In addition, social fitness training that Heroic Imagination Project offers allows us to address areas of weakness (just like we do with physical training). There are 25 years of data showing that we can retrain the brain and utilize and grow group wisdom through this kind of cognitive behavioral role playing.

- What are your strategies for ensuring ethical policies and standards flow down through all levels of the organizing and to all stakeholders?

PZ: One of the strategies we teach at HIP is “courageous conversation”. When anyone in an organization sees something wrong, how can they speak up in a respectful, constructive manner – overcoming any awkwardness and perhaps fear. Conversations can reverse the wrong and even result in appreciation from others for addressing the issue through this respectful oral approach. This affects all levels of every organization. We all can think of times when we witnessed wrong and didn’t act, as well as perhaps how different the outcome is when we do speak up.

- Are there areas you think regulation should be more extensive in regulating corporate ethics? Non-profit sector ethics?

BD: Regulation is important because there should be consequences to wrong actions. For example, taking away certain financial regulations is a recipe for disaster. Concentrated power without checks and balances leads to breakdown: we need systems to address the fact that we are all susceptible to corruption through power. In parallel, we’d still like to inspire people to do the right things because their actions matter.

- Should culture be an important contextual element in ethics analysis? What is unique about the ethical culture and environment in your country that should be taken into consideration?

PZ: Some issues are trans-cultural, for example the impact of the temptation of profit (and greed more generally), social pride, and corporate reporting to shareholders. However, specific cultural norms and accepted practices can be an extremely important consideration. In some cultures, Korea, for example, hierarchy trumps all, resulting in deference to those higher up the organizational ladder and disrespect or even abuse of those below. This can have very costly human, financial, and organizational implications when extended outside the original culture internationally, for example to overseas subsidiaries of a corporation, like Samsung.

BD: Culture is an extremely important contextual element. It is important to understand norms. Are they beneficial to society? How are systems and situations changing our behavior? What are the cultures they are creating (i.e., the outcomes)? How do we change the systems and situations if we don’t like the outcomes?

- Do you think globally applicable ethics principles and practices are possible? Desirable?

BD: I think globally ethical standards are possible and desirable, but I may be naïve and need to do more work with other countries. In general, I believe that strong ethics builds better long-term business models.

- What is the biggest mistake people make in making decisions around ethical issues?

PZ: One issue is failure to consider time perspective. The financial crisis was largely triggered by widespread efforts knowingly to obtain the highest yield in the short-term regardless of the consequences but sacrificing long-term prudent practices of seeking best return under the circumstances. Short-termism is extremely dangerous and almost never the right answer. The future is probabilistic, but it is essential to ethical reflection. In addition, there is a tremendous danger of rationalization. Ethics removed from a situation is clear, but in the situation it is essential to see the language of deception and justifications to make bad things look reasonable. Even Hitler justified his actions as doing God’s work in Mein Kampf.

BD: People don’t think that ethics requires practice, that it is a skill you need to continue to build. For example, we often hear from corporate leaders that they “hire good people” and so they don’t need to attend to ethics. But they need to give people the tools to know how to deal with ethics, above all to step back and pause when there is an uncomfortable situation.

To stay up-to-date with our ongoing interviews, subscribe to the RSS feed for the site (the RSS icon at the top of this page), or subscribe to Susan Liautaud’s twitter feed or Facebook to receive the latest news, interviews, and blog posts.

© Copyright Susan Liautaud & Associates Limited. All rights reserved